Welcome friends! Tucked in Ozark Hill Country, we are a first-generation ranch raising delicious heritage cattle. We value flavor over fast. And sweet community ties. YAH willin’ and the creek don’t rise, the farmstead will be offering other foodie delights, workshops, and traditional skill share gatherings in the coming years. We are situated on 100+ rolling acres in Southwest Missouri near the rural town of Stella.

Seven Sisters: A new print zine series for women serious about food sovereignty in their own homes.

BEEF. Easily the most satiating food ever. Having a freezer full of premium cuts, roasts and and custom ground packages to cook at whim?

AH-maaazing. Feel better, think better, move better. Our beef is loaded with healthy fats, mood-uplifting minerals, and mouth watering flavor.Life feels SO much smoother with a deep stash of delicious meat on hand. Be the home cook brimming with options: sear, slow cook, bake or braise to your heart's content. Feel truly FULL with the ones you love.Ready for whole cow nourishnment?

Our story is best shared through a collection of reflections. We write about our motivations and mistakes, abiding desires, and the hard decisions made as a young family who purposefully moved from city to town, and then sweetly from town to country. Choosing to start a family-scale regenerative ranch is our way of putting down deep roots in the region. We envision Shalah Hills flourishing generationally. By the work of our hands and the sweat of our brows, this is land we are learning how to love well.

13 July 2023

First-Generation Farmer

by Ian Heung

When we first closed on the purchase of our acreage, I kept calling it the property. Or, the even more literal: the land. “Hey! We’re gonna up to the land to play in the creek!” or “Dad’s going up to the property to clean out the barn.” It felt so awkwardly formal to say the property to our then 6, 5, and 2-year-olds. Even our children would wake up on certain summer days and say, “Are we going to get to go up to… the property today?!” It didn’t take much for me to realize that I was just too shy to call it what it really was: a farm.Within the first few months, we enlisted the help of Steve Alarid to help us see the land more clearly. Steve spent 33 years as a forester and firefighter for the US Forest Service working on public lands ecosystem restoration and, after retirement, started Shiloh Native Landscapes to “promote the beauty and benefits of Arkansas native plants.”After spending nearly four hours conversing with Steve, driving with him through all of the pastures, hiking the wooded acres, and climbing the farthest reaches of the property, he looked at us plainly and declared:

“Well, you’ve bought a ranch!”

Oomph, gut check. My brain went on a tailspin: Call it what it is, Ian. A ranch! Wait, does that make me a rancher?! Noooo… (Alexa ran with it right away, and will still at random times stare intently into my eyes, calling me “Ranchero!” with definitive glee.)Before long, however, as is our way, Alexa and I both dove headfirst into our research. For her that meant voraciously finding books on permaculture systems, forest gardening, owning donkeys, and even reintegrating beavers. For me, it meant videos on homestead infrastructure, the virtues of heavy equipment, and how to restore a chainsaw.But, one particular book did grab my attention in an unexpected way. In The Independent Farmstead by Shawn and Beth Dougherty, not only did the Doughertys thoroughly expound on the themes of their subtitle: Growing Soil, Biodiversity, and Nutrient-Dense Food with Grassfed Animals and Intensive Pasture Management, but their no-nonsense, practicality-laden words left me inspired that my thing would be to graze animals on our pastures.I was convinced that I would be able to strategically and systematically develop our (ahem) ranch infrastructure to support the very type of intensive rotational grazing of animals that the Doughertys wrote about. I aspired to build a farmstead that would be self-sufficient and independent by minimizing off-farm inputs (another one of the Doughertys’ core tenets).And so, as Spring quickly came and went and Summer soon took over, I set to work cutting down Eastern red cedars that impeded our fencing, brush mowing numerous pastures that had begun to be taken over by seedlings, and pitching a canvas wall tent on our future homesite so we could spend more hours working while our children work-played. Though as one might expect of a novice farmer, as the summer months locked into their rhythm of thick humidity and heat rashes, my body told me that I had overdone it.While my neighbors worked smart in the relative coolness of the mornings and early evenings, we were commuting from our home 45 minutes away to arrive at the ranch just in time for the hottest hours of the day. Once, I even decided it was too hot, and I just had to brush mow in shorts and t-shirt (chiggers anyone?). By July, I had to tap out and take several weeks off to recover.For some additional context, the previous family that owned this property had not lived on it in over 15 years and, after entrusting the management and baling of the pasture grasses to two kind neighbors, the recent passing of the family’s matriarch led to the five siblings finally selling the family farm. Aside from a formerly domesticated horse that now lived wild on the property, the pastures had not seen grazing in over a decade, and the densely overgrown woods and fast encroaching thorny briars meant there would be much work to do. Not impossible; just work.In August, my irritated skin finally calmed down in time for my parents to fly out from California to visit us for the first time in over a year. They wanted to see the grandchildren, but they also wanted to see this farm that they had been hearing about for months.

Truth be told, I was nervous.

I was nervous about what they would think about this new family endeavor. When my family immigrated to the United States from Hong Kong in the late-80s, I imagine that they never figured their youngest son would leave California at some point and end up in Arkansas with his family.Moreover, I imagine that they never figured that this same son would decide that farm life was for him. And so, as I drove them around the property wishing that it was Fall or early-Winter when the weather was more pleasant and the fallen leaves revealed more beauty and visibility, Alexa and I shared with them some of our plans: a home on a hilltop of mature oaks, cultivating medicinals like elderberries and ginseng, and intensive rotational grazing cattle on our re-emerging pastures. As I continued to show them what we had discovered about our ranch, I felt my nervousness dissolve into steadiness in my voice and confidence in what was laying ahead for us. I told them about the work that we had already done. They saw our children run around creek beds and hillsides with confidence and delight.As I pulled the truck back around to where we had started, I looked intently into their faces, with a Well, what do you think? look on my face. And my dad, a retired engineer that I have learned to trust to always lean towards the side of practicality and prudence, looked at my mom and said:

“Cows, huh? That makes a lot of sense.” And, never missing an opportunity to crack a joke, followed up with, “You can hire me to be your farmhand.”

With a reminiscent smile, my mother shared that while I was driving us around it reminded her vividly of when her father would drive her little-girl-self around their family palm plantation in Malaysia, pointing out details to his daughter about his certain fruitful acres with tender pride. And with that comment, any remaining nervousness disappeared completely. My parents, in their own uneffusive way, had given me all the encouragement and affirmation I could ever want from them. In doing so, they also reminded me that my mother’s father was a farmer and that my father’s family had generations of farmers as well.And, while we may have skipped my parent's generation, I am curiously and faithfully taking up stewarding our family’s farmstead as a first-generation (in a while) farmer.

2 June 2024

Good Things Take Time

by Alexa Heung

The International Slow Food movement was born a month before I was—March 1986—in Rome, Italy. A certain fast food chain was set to open it’s very first national location near the beloved Piazza di Spagna, sparking widespread protest. Instead of vitriol, fists and sign foisting, journalist Carlo Petrini led a group wielding massive bowls of penne pasta before the crowd, feeding forkfuls to passer-byers and chanting:

“We don’t want fast food! We want slow food!”

Despite the delicious dissent, the chain opened and stands today, but with a much smaller “M” sign than planned, as compromise. That gathering though, spiraled into a movement that today extends into 160 countries, fueling multiple initiatives — all centered around traditional foodways, protecting and promoting the dizzyingly diverse array of plants and animals that can nourish us, and the celebration of sensuously unhurried procurement, preparation, and delight in pure food. Whew!Part of their manifesto urges developing, “taste rather than demeaning it” and insists that “our defense (of the multitude who mistake frenzy for efficiency) should begin at the table with Slow Food.. calling for the safeguarding of local economies, the preservation of indigenous gastronomic traditions, and the creation of a new kind of ecologically aware consumerism committed to sustainability. On a practical level, it advocates a return to traditional recipes, locally grown foods, and eating as a social event.”That ethos speaks to us so sweetly here, an ocean away. As a wife, mother, and happy home cook, it seems to me that time and taste do truly belong to one another. Complex flavors are melded at leisure. No buttons, no shortcuts. Daily eating is a tender, personal (oh so relentless!) endeavor. Attention to sourcing the best ingredients our family has access to has built my three babies up robust and true. Memories in the kitchen and huddled around steaming dishes has knit us together fiercely.We envision seasonal feasts and foraging and intimate workshops held here on our land one day —sharing bounty and heirloom recipes and landrace seeds and old-timey skills. All centered around nourishment and exchange and the love of land well tended.

Whatever community develops at Shalah Hills, we want the emphasis to be on savoring and slowing down, childlike joy in natural goodness.

These values led Ian and I to one of the Slow Food Movenment’s ongoing projects—The Ark of Taste—“a living catalog of delicious and distinctive foods facing extinction.” The Foundation writes, “by identifying and championing these foods, we keep them in production and on our plates..” Endangered tastes are detailed in nearly every region of the world, from Aaloo Bukhara Dry Plums of Afghnistan to Spider Flower Leaves of Zimbabwe. Entries are nominated yearly. And yes! much of the fare to be had and hunted for in the Ozarks made the cut: ramps, paw paw, Chinquapin chestnut, Bourbon red turkey, wild ginseng, American persimmon, Arkansas black apple, Barbados Blackbelly sheep, black elderberry, sumac, sassafras, black raspberries—even our hardy Dexter cattle are listed. And though originally developed in Ireland four centuries ago as a perfect tri-purpose peasant breed (milk! meat! oxen!) our growing herd is adapted beautifully to these rugged hills and hollers.We are so new to all this, but are taking the stewardship part seriously. It will take time to clear brush, set fire to certain swaths to return the land to the glorious Oak studded savanna that the Osage maintained so well long before. It will take time for berries to proliferate heavy along the lanes. And for creamy custard-y paw paws to thud softly onto hidden sun-dappled food forest floors.

We will work and wait and sweat. It’ll be worth it.

We have a heart to offer both native and naturalized bounty from our land to fellow homesteaders and foodies alike, especially items with future reproductive or multiplying potential, whether that be bare root, bush, or young healthy livestock.Heritage animals often grow slower (well, let's just say normally) compared to their factory-farmed counterparts. They are often more wild, and wiley, and oh so tasty—having not had their natural foraging, reproductive, and survival instincts selectively bred out for profitability and speed.In just a few weeks time, with a Missouri wildlife breeder permit, I’ll venture into raising up some baby bobwhite quail, which are native to these fields and surely not the first choice for meat birds among the quail options; only owing to the fact that they take twice the time to reach harvest weight than the more popular breed. That might seem foolish for business, but it’s taste and vibrant health we are after as stewards of livestock, little or large. Whatever surplus we end up selling, the same items will be spread across our own family table.I’m grateful Ian chose the word ‘farmstead’ to describe the family venture we are embarking on. It is appropriately vaaaaaague, a perfect umbrella for the things we might get into producing with limited batches. Of course, amazing grass-fed beef shares! But also, maybe jars of pink pickled quail eggs, honeysuckle hydrosols, perennial starts, and black raspberries by the bushel? We do want ramps and ginseng growing sleepily in the shady woods, wild-crafted root beers and vinegars, and succulent lamb, too. Every seventh year we’ll do a full halt on all soil cultivation and production to let our land recoup and rest.I spent my high school years in an agrarian town at the foot of the Italian Alps, as the daughter of a U.S. Air Force fighter pilot stationed overseas. Do you know where the most luscious food memories were seared into me? It was the quiet home cooks that were allowed to take over gas station cafes, the rickety open-air market tables with fresh-picked produce piled high and sun-kissed. The rambly backyard gardens overflowing with figs and dark zucchini. All unassuming nooks and crannies. I remember the intense localism. Regionalism dripping with diverse quirks, small shops crammed with jars and cartons and blooms. The warm stubborn pride. Roadside stalls. Long lingering at the table.

I like what Mr. Petrini did with his bowls of penne. Skipping the protest and going straight for the good stuff. Certain things are incomparable once experienced. Like the first time I crunched a carrot at the Santa Barbara farmers market in college, slapped by how sweet and carrot-y it was, stunned that I had reached adulthood having never tasted a raw root so real.

That’s why we moved out here, drawn out to the country.

Not for a single carrot; but the likelihood that those kinds of experiences will be commonplace for our children. For a quality of life that feels vibrantly straightforward and uncomplicated and free. We are ‘forced’ to fix our own appliances, know our neighbors, read the skies for rain, and move our bodies to improve the precious earth underneath. We are not ‘bugging out’ (although I certainly think there is much more food sovereignty and resiliency and wary wisdom in being less dependent on man-manipulated institutions and infrastructure!). Ian and I were led out here by delight, and beauty, and the space to make, do, raise, tend, grow, harvest. It will be slow-going, soul-shaping work. We know we’re in it for the long haul - as long as we’re called to be rooted here in the Ozarks. So, that orchard I want to plant, teeming with persimmons and pears, just might be more enjoyed by my children as inheritance. Truly, I prefer that.

1 June 2020

Reverse Oregon Trail

by Alexa Heung

29 June 2023 Note: It has been nearly five years since we moved to the Ozarks; three years since my wife’s beautiful chronicling of our journey from California to Arkansas graced the pages of Arkansas Life. In the intervening years, our family has grown and our faith has been sharpened, but discovering our delight in the abundance of this region has not changed. Putting down roots began in the town of Bentonville and, in this next season of life, will continue in the hollers and pastures of our farmstead; Shalah Hills.The “sweet baby” we welcomed to the family in this article is now three. Our “children’s pudgy hands” have become steady instruments of exploration and learning. The friendships and relationships we have cultivated in these short handful of years continue to inspire us. As such, it feels fitting to re-share this story.Kindly consider what follows to be an “About Us,” and yet only a snapshot of us from the recent past. It will be divided up into eight parts (which feels like A LOT!) As a family, it is “parts nine and beyond” that we are excited to discover and share with you all in the months and years to come. —Ian HeungFirst published as “Home to Seed” in the July 2020 issue of Arkansas Life.-------The other morning, my 4-year-old daughter plucked a tiny tender tatsoi leaf from her breakfast bowl, examining it with bemused, slightly cross-eyed glee before munching it whole with an air of giggly triumphant pomp.As her mama, I know the fanfare over such a little flash of emerald was not just from finding a bite of crunchy sweet, but a reminder of our dear friends the Villines who make a beautiful living on the banks of the Buffalo River east of our home in downtown Bentonville. She’s balanced in their trees, hugged their lambs, splashed in their spring, pressed seedlings into their rich soil, sung along to the strumming of instruments in their cozy kitchen. A single baby sprout from their market garden conjures up the lovely world in which it was grown. There’s a certain depth of delight I see in her eyes as she eats the food from our friends’ farm.It’s been two years now since we moved from the San Francisco Bay Area, and we’re still reeling with happy wonder over all the bounty to be had in this region. Much of our greens and meat and dairy—even herbs and flowers, are now connected to faces, places and, most endearing, friendships we’ve begun since we chose Northwest Arkansas as home.

“Let’s drive,” my husband, Ian, declared with a knowing wink, “to let the kids feel the miles. And we’ll have a chance to let it all sink in slowly.”

We decided not to blitz it, instead allocating just a couple hours of driving time each day to coincide with our toddler’s midday naps. We found ourselves doing laundry and dishes in a gurgling hot spring somewhere in Nevada, and by the time we left Colorado, we had stayed at an animal sanctuary, an off-grid homestead and a start-up ranch. When we got too dusty, we’d book a hotel stay until realizing we preferred the rustic wind-rippling of our rooftop tent to hermetically sealed windows. We slept under many skies, feeling perched in a sort of lofted zippered treehouse, and arrived two weeks later in Bentonville, Arkansas, just before the month of July as the day dipped into sunset stillness. Our first hours in town were spent at the Wednesday evening farmer's market at the 8th Street Market. We were graciously gifted a cardboard box of nearly bursting sweet blackberries inside the farm-to-table Mexican restaurant Yeyo’s El Alma de Mexico. “Welcome from our family to yours. These were picked earlier today.”

We were flooded with so many similar instances of casual generosity.

The air of kindness all around town caught us off guard in the best sense, and we dove into meeting new friends. For a while, we were unsure whether we had culturally landed in the South or the Midwest, teetering right on an invisible line. I was surprised to feel a sort of folksy, crunchy, laid-back natural vibe in pockets as we explored the area. Fayetteville felt uncannily like Berkeley to us, the city where Ian and I met and married.Soon, an acquaintance explained that in the 1960s, a wave of “back-to-the-landers” had settled from larger metropolitan cities such as Chicago and New York City all across the Ozarks, drawn to easier access to gorgeous raw land and the freedom to pursue life as they imagined it in a like-minded community. Ian and I glanced at each other and smiled, hearing this bit of history. Though we are not the original hippie settlers from a half-century past, we did come for some of the same reasons—yearning for a slower, nature-steeped, family-celebrating pace of life that would allow us to live more in line with what we valued.A few days later, summer in full swing, we meandered around the farmers market, and I underwent a complete re-education. In California, U.S. Department of Agriculture-certified organic stands are ubiquitous, common. As a dream job throughout college in Santa Barbara, and for a year afterward in Santa Monica, I sold everything from peonies and rhubarb pies to creamy quark and lush marzipan, sun-kissed piles of the best summer stone fruit I’ve ever tasted, working alongside the producers to sell their wares to large eager crowds. But here, instead of clear certifications and a flurry of shorter transactions, I encountered a much slower pace—heartier handshakes, tables adorned with snapshots from pastures and fields, even utterly sincere invitations for us to “visit or drop by anytime.” We were happy to spot moringa bushels and ginger stalks and Thai chilis, more growers selling fresh Asian vegetables than we ever had access to back in the Bay Area, thanks to many Hmong farming families in the region. I was wowed to realize that the majority of the vendors were only traveling, on average, 30 minutes away compared to the upward of seven or eight hours I was accustomed to in California, where the markets were much more bustling and businesslike in their exchanges.Despite the relaxed ease and friendliness, I was still a bit thrown off while browsing the stands. Some strawberries in cute cartons looked gleamingly good, but I eyed them with hesitance, as they are a notorious crop for high pesticide use and usually stay persistently perched at the top of “the dirty dozen” list. The term “local” only meant so much to me as a curious newcomer. At the Brightwater food truck, a sweet chef listened intently to my confusion and blurted out breezily,

“Oh! You’re looking for Certified Naturally Grown!”

I learned that CNG is hailed as a “grassroots alternative to Certified Organic” and is peer-approved, far less prohibitive in membership cost and requirements, and, in some cases, even holds higher health standards than the USDA equivalent.One of the first memorable conversations I had at the market was with Jennifer of R Family Farm, and we somehow got on the topic of food as medicine. From behind her table she laughed aloud divulging, “I told my then boyfriend (now husband) that I’d only marry him if he chose absolutely any line of work beside chicken farming—which my dad did and I know firsthand how bad it was. And look at us now!” In a single generation, she and her husband diverged from conventional practices to sustainable and regenerative ones. Their pasture-raised meat is extremely popular and seemed to be practically flying out of their trailer’s massive deep freezers and into their customers’ waiting arms. As we spoke, Jennifer admitted that some rare passersby do scoff at their prices, which reflect a fair rate for meat raised right. Afterward, in a sort of hushed humility, she whispered,

“I just don’t believe you can just eat whatever you want and say, Lord heal me.”

That Fall, when the farmers market shuttered for a long offseason stretch and we saw persimmons and squash appear, we got a first brush with seasonal scarcity: All the abundance of the summer harvest tapered off, and there was a reassessing of what could be found fresh and close.

Accustomed to the perpetual sun of the West Coast with its 365-day-a-year growing capacity, we were scrambling for wool mittens and boots in a hurry.By the time our first spring in Arkansas arrived, we had gotten ahold of a Baker Creek Seed Catalog. Armed with a huge stack of saved cardboard egg cartons, we began the process of growing heirloom food from colorful promising packets. My littles and I were hooked at the emergence of the very first sprouts pushing their way millimeter by millimeter under our giddy watch. Not all survived, but the ones that did delighted us so much. Within a few months, there was an explosion of herbs and rows of ripening tomatoes in our care. Without any canning know-how, I had to agilely oven-roast and freeze jars instead. We gave dozens of homegrown wildflower bundles away in flurries, along with baskets of surplus peppers and greens. My children’s pudgy hands learned to prune and water and plant with delicate determination but, most of all, to wait and watch what weekly summer storms and compost and scorching heat could produce in our backyard allotment of earth—our beloved trial-and-error victory garden.

Many months passed, and now into our second fall, slower than a seed, my belly started swelling with our third child.

Air, water, food, light—these four necessary elements are always on a mother’s mind—for herself and the little ones she leads. For me, this means windows flung open to the breeze, fetching live spring water, large pots stirred and left to simmer, bare faces turned toward the sun.We’re only one family, but I sense a real invitation to support businesses we believe in and practices I want to see multiplied to contribute to more regenerative foodways. In every place, there is beauty and blight. Fake food. Food insecurity. Genetically modified franken-food. Food deserts. Many unnatural and engineered ickies that put profits over people. So when we heard about ventures like The Berry Farm in Centerton that turns their sheep out to munch on grasses beneath their blueberry bushes, where others might have reached for an herbicide, we are all there as patrons filling boxes to the brim, especially when 100 percent of their proceeds benefit a program that provides vocational training for orphaned children. We want to be a part of heartening and hopeful initiatives.We’re grateful for Red Barn delivering blue eggs and edible flowers to our doorstep. Osage Creek Farms was willing to save suet from its herd, allowing me to render huge batches of healing tallow balm. Rosalba of Mama Z’s niximalizes her corn to create incredibly moist traditional masa in a range of lovely hues. I think about the happily pastured lambs at Hanna Ranch. The wildly delicious log-grown shiitake mushrooms from Kingston’s Sweden Creek Farms. The smokey wood-fired sourdough boules from Sylvan Artisan Bread. Joyful Valerie Esparza supplying us with creamy and decadent raw jersey cow’s milk in frosty, clinking half-gallon mason jars. The list could go on and on, of farmers and makers and passionate folk honed in on offering really pure, earth-honoring products. Many evenings, we look down at our plates, and they’ve become a map, a fresh mingling of the best ingredients we’ve been blessed to source. Sometimes it even becomes a game before grace is said as we nudge the kids to connect the people they know who are responsible for the ingredients they’re about to enjoy.When we moved here, I think we were craving the connection that a small town like Bentonville affords. From the onset, yes, we prioritized filling our bellies well as we set down roots, but what we ended up discovering was just how intricately woven food and family could be.

A big part of becoming “Arkansan” for us meant going beyond knowing “where our food was coming from” to knowing many of the hands and hearts responsible for it.

Relationships blossomed as we looked ardently for sustenance grown or raised right. The products we found had stories, faces, friendships awaiting. It’s rarely an anonymous exchange when quality is sought out— someone stands proudly beside it - with lots of sweat and toil and glory alongside the goodness.As I write, it’s been just a few days past two whole years since our move. Our children are ruddy and flourishing, and we just welcomed another sweet baby into the world, currently cocooned inside. One day, I see her finding her own way to celebrate life like her brother and sister do. The older ones can catch themselves a crawdad. Slip in and out of a hammock with ease. Cycle fearless on flowy forest trails. Identify birds and trees and all manner of flowers beneath their bare feet. Dance and splash under a thunderstorming sky. They are kind, and fiery in their fighting, but know what forgiveness means. And especially, hallelujah—how to enjoy a raw turnip plucked straight from the ground, shined up, before being crunched, on the pant of their overalls.

30 April 2024

So You're A Cattleman

by Ian Heung

“Oh, so, you’re a cattleman.”

Remarked dapperly dressed older gentleman sitting across from me. His attire was a mix between an old sailor and how one might picture an Ozark mountain man, full white beard and all. Our mutual friend, Mark, had just introduced me as his other friend who also owned cattle. For some reason, though, being called “cattleman” caught me off guard.“Uhh, yeah. I am. But, I’m still new to it…” I fumbled, intentionally understating things and certainly not drawing attention to all I had learned over the last year. The learning curve had certainly been steep.Fifteen months earlier, I was chatting with our dear friend Joe and, in passing, he shared that they had been gradually bringing their cattle to the sale barn—circumstances had made it necessary to disperse their larger animals and focus on their sheep. They were down to their last cow-calf pair, along with a 19-year-old Paint Horse that had been sorely attached to the now dwindled herd, and were trying to figure out what to do with the horse if and when the last pair was brought to town.

“What if we bought them from you?” I blurted out; half offer, half question.

(As in: “Would it be totally ridiculous if I took stewardship of the animals considering how little experience I have?”). I knew that the fencing on our property hadn’t been tended to for over a dozen years. Yet, this was not a fully spontaneous decision. Ever since we bought the ranch, I had known that grazing animals would be my thing. There would certainly be many other farm-y things to do, but owning livestock and building soil and grass health via graze-poop-and-repeat felt obvious to me.And so, I set out to prepare our first pasture to receive the three animals. I set up electric cross-fencing, figured out how to get water down to the furthest corners, grateful that Winter was more going than coming. On the last day of February 2023, we welcomed the Angus-Gelbveih cow, her bull calf, and the old Paint into their humble new digs at Shalah Hills.By the end of March, I had logged some serious miles as I was still commuting between home and farm. From the jump, the two Angus-Gelbveihs were determined to be anywhere but inside my pasture, and I had an old Paint walking circles looking for his missing friends. By April, those two cattle were living full-time across the road with my neighbor Terry’s herd, every vulnerability in our fencing was revealed, and we made plans to butcher the bull calf and sell the cow. Even those plans were thwarted (sadly) as the cow just keeled over as Terry attempted to load her. Some combination of what these two animals were used to (widely roaming along the Buffalo River) and my own inexperience made this first foray into animal husbandry feel like a failure.

Making meaningful mistakes, however, was something that I preached and practiced in my career as an educator.

As Spring approached, undeterred by these previous misfirings, when our friend Valerie shared that she was selling her cattle—this time a trio of heritage Irish Dexters—we jumped at the opportunity.We quickly noticed them adapting to their new surroundings; their gentleness with us and our children. Dexters are a hardy breed that have been raised for their sweet and tender meat and creamy milk for four centuries. Small (not miniature) and dual purpose, Dexters are keen browsers, their diverse pallets enable them to have a “diet of wild herbs ensuring the product is rich in CLA, Omega 3, Omega 6 and Omega 9.” (Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity, Ark of Taste)The horse had new friends and now with our starter herd and a clear purpose, building pasture health and growing excellent grass, I began rotating them every chance I got.I practiced using reels of polybraid electric fencing along with step-in posts to move the herd from paddock to paddock (a technique mastered by the Kiwi-ranchers of New Zealand) in order to bring them to the freshest forage and away from their manure. I built a roving mineral feeder that gave the animals free choice of mineral, salt, and kelp to supplement their grazing diet. I learned to leave one of our pastures ungrazed, those grasses would serve as standing stockpile for the Winter, a system that in theory would allow me to use little to no hay bales in the coming months.By mid-Summer, I had them on a comfortable rhythm, and so we added a Dexter bull to enable breeding. Simultaneously, I was learning to read our pastures. Poison hemlock, bull thistle, and perilla mint had to be cleared. Broom sedge and bramble had to be managed to give way to clover and other tasty legumes. With our standing forage stockpiled and our stock water system winterized, we witnessed these Dexters live up to their reputation, preferring snow over the warmth of a barn. They grazed that Winter forage down, our back-up bales went mostly unused, and we saw them reflect the hardiness and durability of their breed.Winter did not, however, go “oh so simply.” An older heifer had showed inklings of over-eagerness and fence-testing since we got her. Choosing previously to overlook some of those behaviors because she seemed otherwise sociable and sweet with us, as Winter came and slowly moving through stockpile tested the heifer’s patience, she began forcing her way through electric fencing. One escape. Two. A third; this time knocking down the fence line that broke the entire herd out. Then the final straw: one snowy evening, she broke through our goat pen, only for me to find the goats cowering in the corner of their shelter the next morning, as the heifer munched on their hay. A phrase echoed in my mind, one that we have now heard on several occasions from old ranchers and newer graziers alike: “There are too many good cows out there to keep the bad ones.”I don’t believe in declaring anything—let alone an animal—“bad,” but this was just plain stressful for our family, each time bringing the heifer and the herd back to where they were supposed to be, patching or resetting the downed fence.

It was at this point that I had to “CATTLEMAN UP.”

Continuing to overlook her less-than-ideal qualities would be a liability for the rest of the herd. Even if I could continue enduring the fence-testing, it is not uncommon for cows to teach and pass behaviors onto their calves. At the same time we noticed that our freezer stores of beef were dwindling. It was time for our first cull.Knowing that our friends, Cuyler and Maggie, had home butchering expertise, we hatched a plan with them to harvest at our farm, taking advantage of Winter temperatures. On a cold sunny day, as she was munching on the overflowing bucket of organic alfalfa—her favorite treat—that I used to lead her far away from the herd, I dispatched the heifer with a single round. As she instantly dropped, I was confident that her last registered moment was one of busy delight. Much work ensued but, in short: The meat was absolutely delicious; a testament to a life well lived. Zero stress, in a familiar place. Alexa and I were surprised by how solemn and celebratory the experience was.

It’s hard to explain, but it felt right it was done on our soil—honoring, complete, pure. Not too long after, I received a text from a dear friend whom we had passed along some steaks to:

“Easily the most juicy and delicious piece of meat I’ve ever had! Phenomenal flavor and texture. I would definitely 100% buy from you at market price if you are willing to raise it.”

If you know this friend—the seriousness and care he has for food and, frankly, his brutal honesty—you would know that his words meant so much to me.Hearing him echo our own thoughts about the tastiness of the beef validated all that I had learned and practiced during that first year of ranching. It was a huge boost of confidence, especially knowing the plans I still have for optimizing our operation, improving infrastructure, and forage diversity. It also helped me to zero in on my goals—it was go time: Grow the herd. Don’t overtax the pastures. Find the sweet spot to enable the land to flourish as they rotationally graze.. focus on raising delicious and nourishing meat for our family and others.

20 July 2023

Healing Grasses

by Ian Heung

This is a topic that I have often spoken about with close friends or folks that have expressed a desire to really get to know me. For reasons that will become obvious, however, it has taken over five years for me to properly spend time journaling about these experiences for more eyes to read.Exactly six summers ago, our family arrived in Northwest Arkansas after a two-week road trip camping through the Rocky Mountains and across the Great Plains. We were dusty and worn from the drive, but those two weeks were full of adventure and sweet memories for our family.“Let’s drive to let the kids feel the miles. And we’ll have a chance to let it all sink in slowly.” I remember telling Alexa just before we set off.

But, embedded within that desire to sleep under the stars and take things slowly was the unspoken fact that we just needed to get out and process our pain.

What needed to “sink in” was all that had just happened to us—we needed space to make sense of the unexpected trauma that precipitated our decision to uproot our family from all that we knew in California.Just five months prior, in February 2018, Alexa woke me up in the middle of the night because our one-year-old was vomiting for the first time in his little life. Within a couple of hours, my daughter and I were throwing up too. Perplexed and with a vague feeling that there might be something awry, we decided to pack a small bag of essentials and left to spend the night with my parents.

Little did we know, my wife and children would never step foot in that house again.

Our home was hurting us. We were certain that the maintenance guy our property management sent, just days prior, to fix a water leak under our kitchen sink had instead opened up (and exploded a grenade of) mold spores into our air. A remediation assessor was sent out the next day and informed Alexa that the subfloor underneath was soaked and buckled—and likely had been festering for a long time. The leak had been reported since that prior September and, in the meantime, we had tried our best to mitigate any water damage. Looking back, we were completely naïve to the danger of prolonged water damage and should have pressed even harder than we had been for it to be addressed. We soon confirmed through a battery of air and surface tests by a certified industrial hygienist we hired that the mold and mycotoxin levels in the home were so dangerously high we would be foolish not to litigate. And, so we did.If that wasn’t already complicated enough: Our property management was also my employer. The very people that ran the boarding school where I taught for the last seven years and where I brought my family to live on campus as a residential faculty member for the last three, were inexplicably turning a blind eye to the seriousness of the circumstances we were uncovering. We felt like we were being brushed aside and that the situation was being minimized; they made us feel like we were the problem.When we felt like we had exhausted the extended stay with my generous parents, we strung together a series of Airbnb stays while trying to find answers to the physiological responses we were having to the toxins built up in our bodies and attempting to normalize homelessness to our children (and ourselves). Before we fled the home that day, Alexa was having the hardest time of all, having been unexplainably sick for almost half a year, with many “professional” opinions alluding to postpartum depression. But with daily anxiety attacks, extreme chemical sensitivities, waves of exhaustion, and mental lapses, she knew it had to be something else entirely, “I’m not totally hopeless. I’m just so sick of feeling sick.” She was on the brink of despair and I was just trying to hold it together and put on a brave face.

I was still gainfully employed, but we were draining our savings and having to explain to our 2- and 1-year-olds why they didn’t have some of their things and why (as advised by our lawyers) we weren’t ever going back to get them.

The most painful memory, to this day, was waking up to my wife having an asthma attack (the first one since before college) because she was having some sort of acute respiratory reaction to the Airbnb we had just moved into earlier that afternoon. At 2 am, after packing all of our things quietly back into our car while Alexa tried to calm her wheezing, we transferred our children to their car seats so that they could continue sleeping while we drove around attempting to find any hotel that would still be open. We drove from one extended-stay hotel to another to either find that they had no vacancy or we were worried that something in their rooms might trigger another respiratory attack. So just after 4 am, exhausted and defeated, we pulled into a friend’s driveway, pitched our car’s rooftop tent so that we could sleep, and texted them so that they wouldn’t be surprised in the morning.We were feeling desperate and confused at how our bodies were responding. It was at that point that we realized we could do nothing else but distill life down to the essentials. Food. Water. Air. And, while we didn’t understand everything that was going on, Alexa and I reminded each other to fear not. Somehow, while barely grasping onto any sense of normalcy we could, we knew the Father was calling us to respond with faithfulness, not fearfulness.

That became our warcry: walk in faith, not in fear.

Alexa wanted more than anything to just stand barefoot, grounded, on healing grasses. She knew her body was slowly and steadily releasing the toxins, day by day. We knew we needed to get out of the urban environment, and seriously contemplated the idea of WWOOFing across the country or overseas with our young family, but ultimately found an opportunity to move and continue teaching in Arkansas; The Natural State. It wasn’t organic farming, but it would be more rural, we told ourselves. And so, through the heat of the summer, we drove from campsite to campsite, charting our course from spring water to spring water, from natural grocer to natural grocer. Food. Water. Air.We arrived with just eight boxes. Just the things we fled with that February and some additional necessities we had accumulated in the months of nomadic Airbnb-ing. I did briefly go back into that moldy home once more in full hazmat coveralls and respirator to recover some essential documents, but we never did recover the vast majority of our belongings.

When we were feeling most vulnerable, I would remind Alexa over and over: the most important things got out—us.

In our new home state, we prioritized splashing in all the flowing water we could find, eventually renting a home on an acre with some chickens. Later on, an opportunity arose to rent near a park with a spring-fed plunge we loved, so we moved closer to town, immediately asking the owner if we could rip up the sod in the backyard and plant our first garden since moving.While we weren’t yet farming, we were sowing, we were tending, we were harvesting. Bearing fruit didn’t necessarily mean we were thriving, because in many ways we were still just surviving. It meant stewarding what little plot we were blessed with and walking in faith knowing that the Father would provide. A settlement was eventually reached, which amounted to paying the lawyer fees and barely moving the needle on our other transitional expenses. It took over a year before Alexa felt that her body had physically recovered; years until our hearts did.And then, in what I can only characterize as heavenly provision—divine providence—just over a year-and-a-half ago, we found the farm. Peaceful pastures, mature hardwood trees, and gently flowing creek waters.We decided to call it Shalah Hills. SHAW-LAW means tranquility, rest, quietness—from the Hebrew characters shin-lamed-hey. Shin (an ancient Paleo pictogram for the two front teeth), meaning to crush, destroy, press, devour, consume. Lamed (a pictogram for a shepherd’s staff), meaning everything from gentle guiding discipline to a forcible taking. Hey (a pictogram for a man with outstretched arms), meaning breathe, revelation, behold, wonder, exclaim.As we studied these three root characters, our story came out in the name. Shalah. Drawn out for one's own good; an almost violent removal for eventual prospering. The aftermath of being plucked out of fire or destruction; to be delivered into safety.

Shalah Hills. Our own peaceful, healing grasses.

100% German Shepherd Puppies from our homestead to yours!

—> Asking modest rehoming fee: $300

Ready for their new home starting October 1st, 2025Healthy, living fully outdoors, robust, no vaxx or meds at all. These are un-papered, un-registered stock. Super vigorous, chubby, and nursing wellWorking parents have great qualities, providing our family with essential protection, vigilance, and intelligent, loyal companionshipJuniper (mother) has silver sable coloring and is the prolific hunter on the interior of our property, very protective and doting mama, with a remarkably mellow and calm disposition. But also super obedient and playful too! She lives to be chased.Finn (father) is black and tan, super strong and fit. Sweet eyes. He provides a perfect intimidating ‘welcoming party’ presence roadside on our farm. Truly loves to be pet and is unrelentingly eager to please. Everyday life goal: play wrestling with his mate.

Last year’s litter pics. The very 1st batch:

Juniper and Finn's second litter born July 28, 2025 -

The parents on the 1st day meeting one another -

Call or text Ian at (510) 734-7232 to visit and purchase one of these beautiful sweet puppies ready for training for your family’s future protection & fun! We love and are so grateful to our German Shepherds and what they provide us. He’ll be able to give you an update on gender / coloring and the latest ones still freshly available!

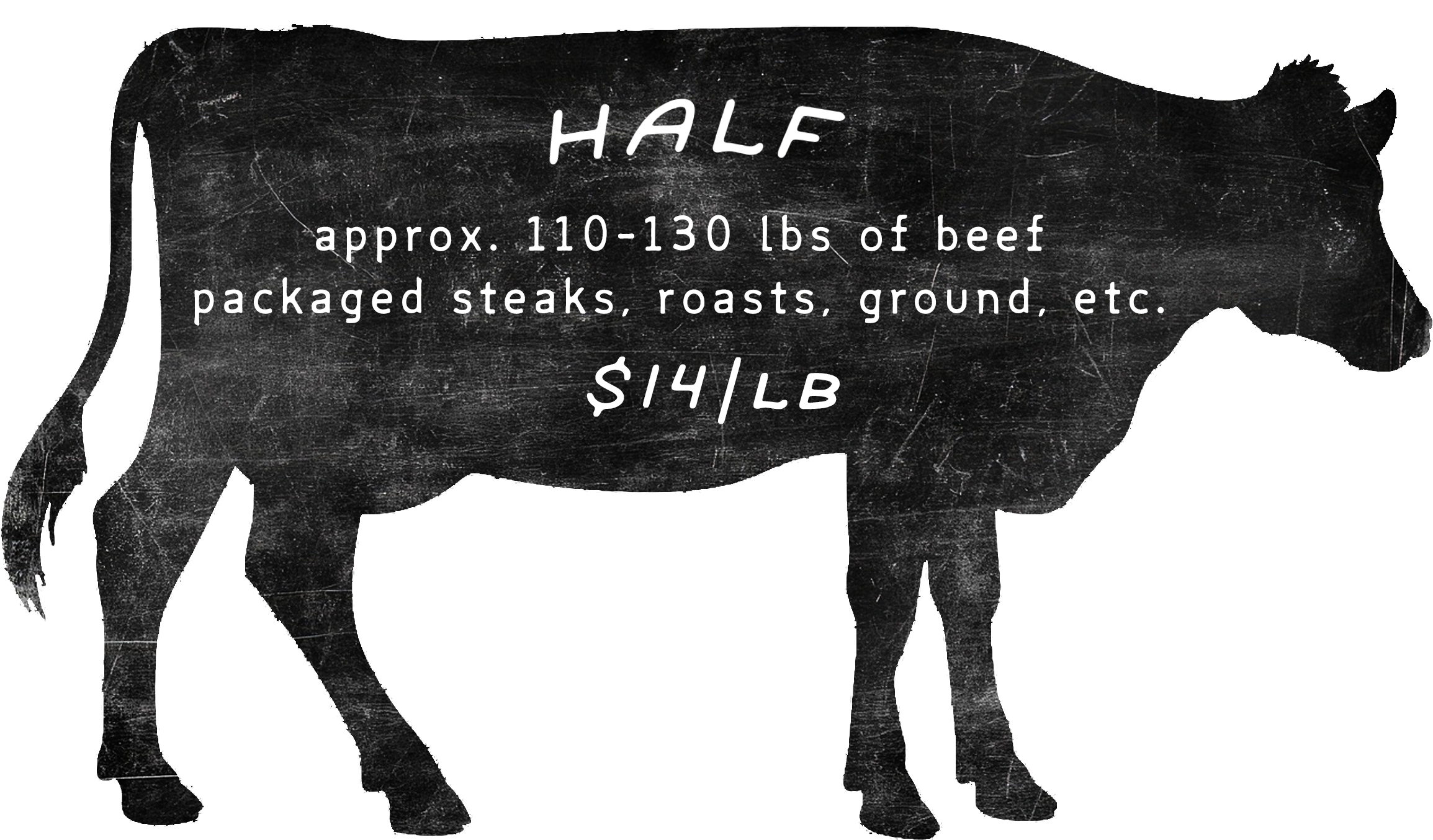

Providing our family with cost-effective, nutrient-dense, and oh-so-satisfying nourishment just makes sense. In some ways, it set the gears in motion for us to become ranchers.We acknowledge that this a big purchase so we are here to walk you through the process.

Sought after for being naturally sweet + tender and rich in CLA, Omega 3, Omega 6 + Omega 9 fatty acids, Dexter beef is special stuff.A ranch in Michigan did a deep dive on the breed:

Discover the Superior Taste and Benefits of Dexter Cattle BeefWhat makes Dexters biologically special?

Britain’s Dexter cattle: Tiny breed, big-flavour beefPacked with minerals, our herd of Irish Dexter cattle are 100% grass-fed + finished and rotationally-grazed on diverse, healthy forage; resulting in meat that is deeply nourishing and loaded with vitamins A, D, E, and K.

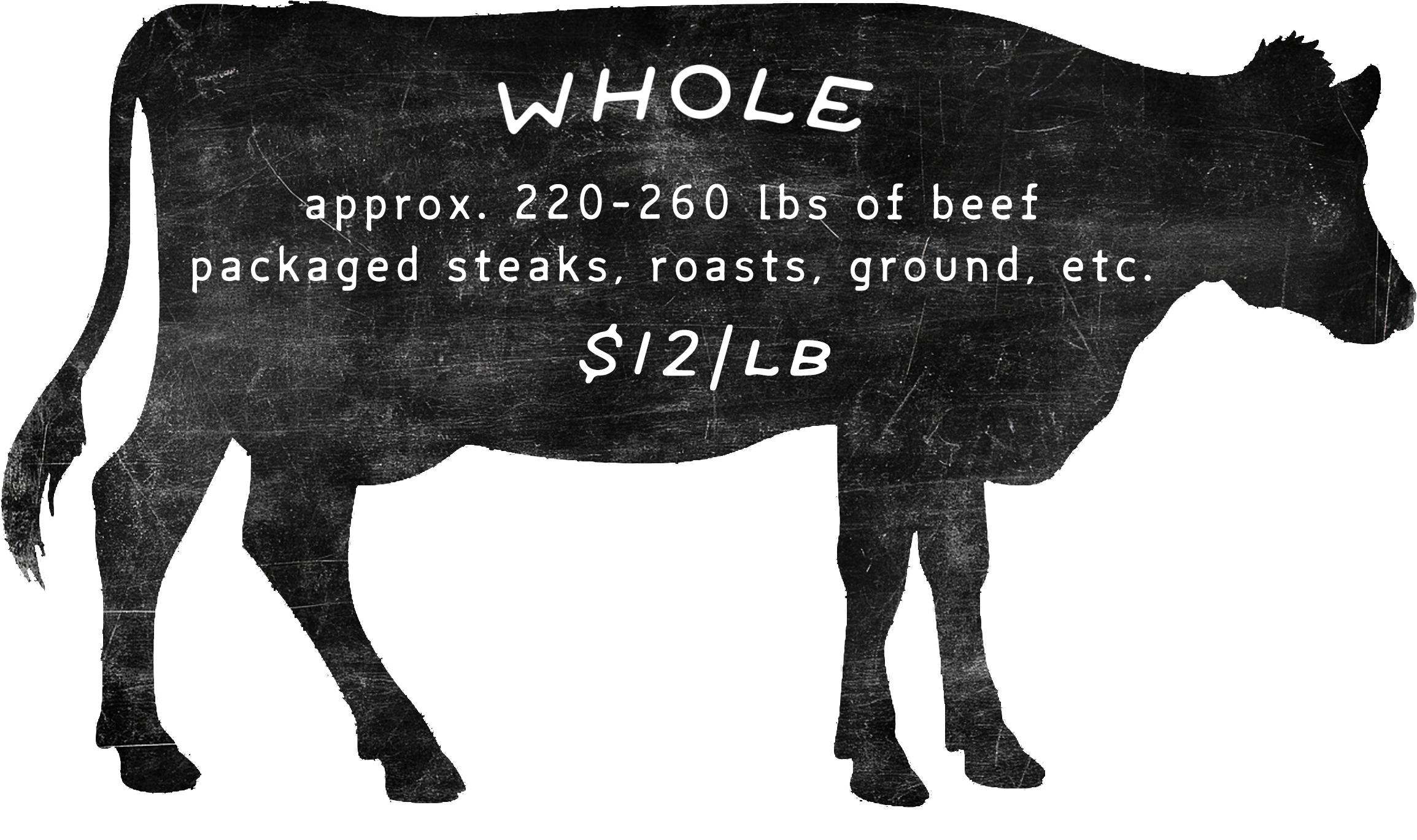

Terms like "live weight" and "hanging weight," and costs that separate processing fees are helpful to the farmer raising the animal. While we understand why things are typically done that way, we want our customers to know exactly what they're getting.Our per-pound price is calculated based on the amount of packaged meat you pick-up. All processing, packaging, etc. fees are folded into this price.

Spring / Summer 2025 Pricing

We are genuinely delighted to have you as a customer!A 50% deposit will secure your reservation and set the gears in motion, enabling us to solidify the processing and pick-up dates and work with you to identify your desired cuts, making sure your family is ready for some tasty beef coming your way.Reach (back) out to Ian to get started.You can call or text (510) 734-7232 OR continue the method of communication that you've already begun.

Discover the Superior Taste and Benefits of Dexter Cattle Beef:

Is this the World’s Best Beef?

When it comes to beef, Angus beef is the most recognizable and popular breed of beef cattle in the United States. Is it the best? Some suggest that Wagyu is the world's best. Still others, including world renown chefs like Gordon Ramsay and Jamie Oilver, indicate they've found something better...and just like diamonds... it comes in small packages.Introducing Dexter cattle.Today we will attempt to summarize the beef qualities of Dexter cattle.We could write many words describing the other fine attributes that make Dexter cattle a super breed, but we will save that for another day.Briefly, aside from great beef, Dexter cattle are hardy, more efficient at converting a variety of grass/forage to beef, produce more pounds per acre than most any other breed, are great mothers and have a calm disposition.Now, on to the meat itself…

Tenderness

That essential characteristic that determines the ease with which each bite yields, is intricately linked to the collagen structure and the size of muscle fibers.Dexter cattle feature smaller muscle fibers that naturally pack a denser punch. The outcome is a consistent texture that makes it easy to chew.Nevertheless, the fat of some other breeds of cattle can sometimes contain a substantial amount of collagen, which can potentially hinder the dining experience.In contrast, the marbling in beef from Dexter cattle is celebrated for its distinctive "spider web" pattern, which is widely regarded as a mark of premium quality, characterized by its low collagen content.

Juiciness

A hallmark of exceptional beef, can manifest in two primary forms—water-based and fat-based.Dexter cattle boast an abundance of red blood cells, a legacy of their milk-producing lineage.This abundance translates into a naturally darker muscle color and a lower pH. The presence of ample red blood cells means more oxygen, even after the animal's demise.The postmortem respiration of the animal meat activates the production of lactic acid, which contributes to the preservation of the meat's natural fat flavor.It also facilitates the binding of water within the meat and leads to the breaking down of muscle proteins, ultimately enhancing tenderness.

Let’s get a little deeper.

Animals store a combination of compounds in their fat, including flavonoids, pheromones and hormones, which can impart undesirable flavors.Dexter cattle, interestingly, tend to stockpile fewer of these unpalatable elements in their fat.As a result, they display a pristine white fat cap, even when raised on a grass-only diet.This crucial distinction means that the fat from Dexter cattle has a minimal impact on the overall flavor profile of the beef.

A Premium Experience

In essence, Dexter cattle offer a premium dining experience due to their unique blend of physical and biological attributes.Dexter cattle beef is characterized by its juiciness, rather than greasiness, thanks to the pH levels that facilitate moisture retention during the cooking process.The flavor is rich and pure, unmarred by excessive fat or off-putting flavors that can be associated with fat.The meat's even texture, a result of smaller, denser muscle fibers, coupled with the pH levels that enhance tenderness contribute to its deliciousness.These factors consistently merge to produce an exceptional culinary journey.It's worth noting that not all breeds possess the same winning combination of attributes, and even if they do, these elements may not always harmonize in such perfect synchrony.Thus, Dexter beef stands out as a breed that consistently delivers a premium dining experience, characterized by these distinctive qualities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Dexter cattle beef offers a truly exceptional dining experience, with its unique blend of tenderness, juiciness, and pure flavor. These qualities, rooted in the breed's physical and biological attributes, consistently elevate Dexter beef to a premium level, making it a noteworthy choice for discerning culinary enthusiasts. Dexter beef has outstanding quality and tastes the way beef used to taste.

Britain’s Dexter cattle: Tiny breed, big-flavour beef

from Metro magazine, republished 2019

Dexter may be the Shetland pony of the cattle world but the breed produces some of the most tender, intensely flavoured beef you’ll ever eat.Charlie Lakin’s search for the best beef in Britain has driven him round the bend, literally.Di Smith’s nationally renowned ‘Moomin’ herd of Dexter cattle is separated from Lakin’s restaurant kitchen at The Marquis in the Kentish village of Alkham by just one hill and a third of a mile of gently winding road.When I meet the chef, he’s at the farm’s small shop busily butchering a forequarter of the meat into cuts including chuck steak, ribeye, brisket, blade, small flank and shin.‘It’s very therapeutic – to come down here and get away from all the argy-bargy of the kitchen and all the stress, it’s absolute heaven, I love it,’ says Lakin, a farmer’s son and Yorkshireman who has only been cooking Dexter beef professionally since he took over the kitchens of The Marquis in 2008, despite eating the meat from an early age.‘I was brought up eating Dexter beef. My mum and dad are members of the Dexter Cattle Society and my dad has actually got one of Di’s breed in his herd,’ says Lakin.‘My dad had always talked about Moomins but it didn’t really twig with me until I moved down here and started using the meat that this was the Moomin herd everyone had gone on about.’Smith has been raising Dexter cattle, which originated in Ireland and grow to about a third of the size of Friesian, for more than 20 years and is a former president of the Dexter Cattle Society.Her Moomin herd currently numbers 98 head of cattle, which graze freely on the herb-rich pastures of her Sladden farm in the Alkham Valley, a diet supplemented only with hay, sugar beet and the occasional French stick as a special treat.‘The natural feed makes a massive difference to the quality and the flavour of the meat because they haven’t been forced to bulk up quickly like intensely reared animals,’ says Lakin.‘Without a doubt the meat is definitely richer, you can really tell the difference.’Smith says there’s another reason why the flavour is so good.‘The big difference is the muscle fibres.‘If you’ve got a huge beast like an Aberdeen Angus, you’ve got the same number of muscle fibres but they’re much, much bigger.‘Because the Dexter is smaller you get very fine graining, which will help keep the flavour. It’s just more intense – it’s like a good wine.’Smith’s natural method of raising her herd also allows much more time for that flavour to develop, with the animals being killed from about 24 months up to the legal limit of 48 months.‘Intensively farmed animals are killed at ten to 14 months – the quick throughput is why you get the big continental beasts,’ she says.‘But fashions are changing and people are looking at better quality.‘Each animal might mature at a different time and it’s my job to see when it’s ready.‘You have the growth time, when they shoot up, and then they plateau – that’s when they get nice and chunky, and that’s when they’re fit for killing.‘Intensively reared animals are “finished” by feeding them with barley so they’ve got quite a lot of fat and trans-fats on them.‘Ours are grass fed so they have far more omega-3 in the fat, which is a good thing.’Lakin’s approach to cooking the meat is equally distinctive.While familiar cuts such as the fillet are included in Smith’s local meat box scheme (and also available one Saturday a month to passing trade), the chef is interested in the more arcane parts of the animal.‘A butcher would trim the flank and mince it but it’s actually a gorgeous piece of meat and I like to slow-cook it,’ says Lakin.‘The collar would be diced for stewing beef but I like to trim the fat away, maybe soak it overnight in Dogbolter, a rich thick dark porter ale with a load of herbs including thyme, then sear it off and braise it in the marinade with some stock.‘I gently roast the bones so the fat renders off and we get big vats of dripping, which is great for slow cooking and roast potatoes.’I join Smith in the dining room at The Marquis for a taster plate of Dexter beef that includes pan-fried ribeye with sautéed mushrooms; slices of salted silver side brined for a week in salt, Demerara sugar, coriander, caraway, bay leaves, garlic, black pepper and cumin, then poached with onions, carrots, celery, coriander seeds, cloves and other spices; and croustillant of shredded flank bound with onions, coarse grain mustard and brandy, and deep-fried in filo and string potatoes.It’s a tour de force of cooking but one that pays proper respect to a superb raw ingredient.